By/ Gulf International Fourm

SOme videos in this commentary include content that the reader may find offensive or disturbing.All videos featured in this commentary have English captions. Please select “CC” on the YouTube screen to view subtitles

SOme videos in this commentary include content that the reader may find offensive or disturbing.All videos featured in this commentary have English captions. Please select “CC” on the YouTube screen to view subtitles

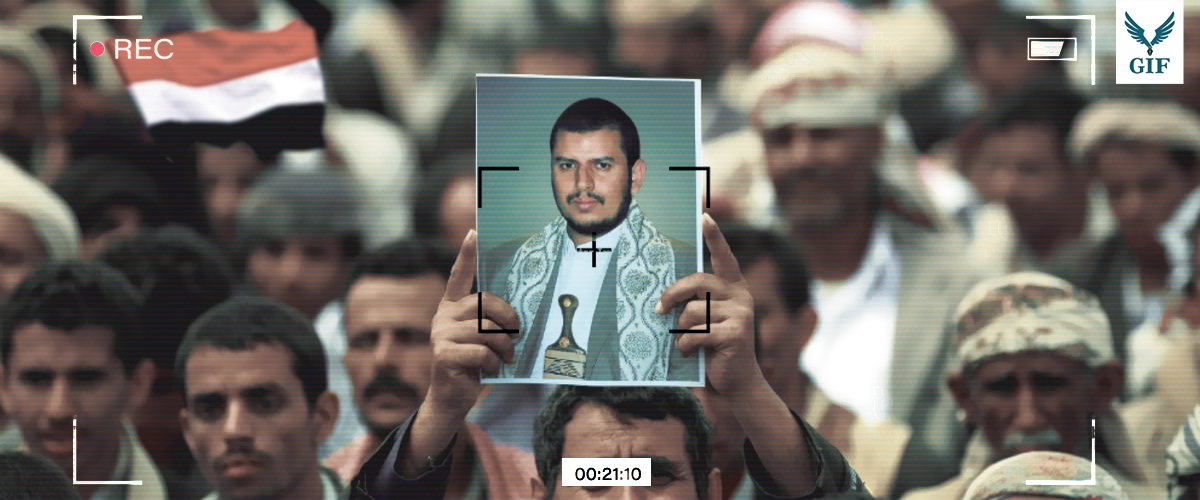

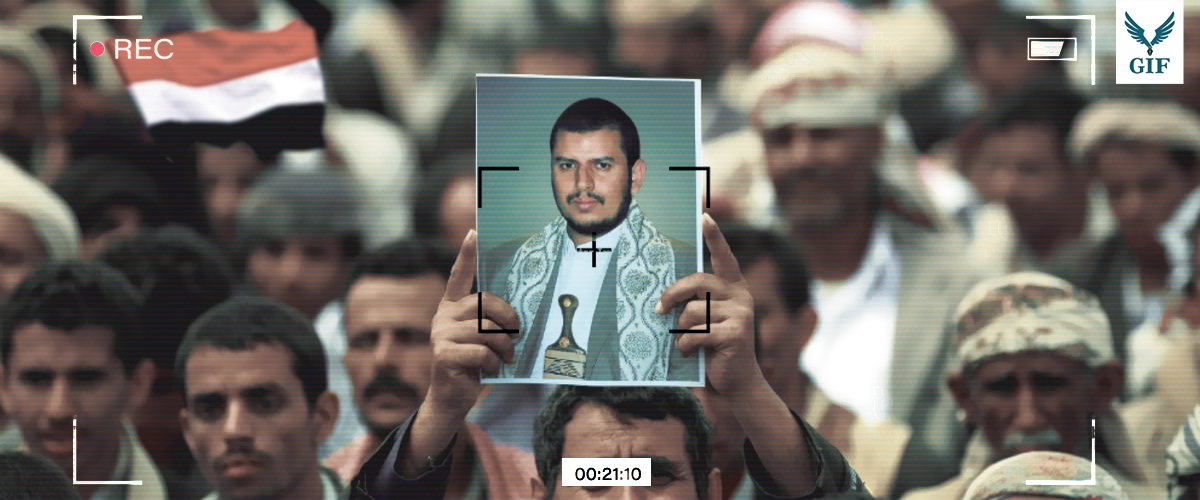

In January 2002, Yemenis from the northern city of Sa’ada crowded together in an auditorium to hear the first in a series of lectures delivered by Zaydi religious leader and former parliamentarian, Hussein al-Houthi. The lectures were publicized as lessons in Qur’anic guidance, but they often included political commentary. Al-Houthi’s first lecture attacked international news outlets for their unwillingness to sympathize with the plight of Muslims and Arabs worldwide. The global media, al-Houthi asserted, was fueled by conspiracies and not to be trusted.

Al-Houthi was assassinated by former Yemeni President Ali Abdullah Saleh’s forces in 2004 and never lived to see the impact of his messages. Through years of conflict with Yemen’s government and foreign militaries, the Houthis (also known as Ansar Allah) evolved from a localized movement in Sa’ada Governorate into the dominant power controlling most of northern Yemen and operating several news organizations. Today, Houthi media is diverse in its subject matter and targets a wide range of audiences across many platforms. An examination of Houthi messages provides us valuable insight into their objectives. Among these objectives is the group’s desire to be seen both as a popular grassroots movement concerned with human rights, and as the legitimate government defending Yemen’s sovereignty.

The little attention that is given to Houthi media in contemporary analysis tends to focus on military developments in Yemen’s war and, occasionally, political speeches delivered by Hussein’s successor and half-brother, Abdulmalek. But the group’s content production is rapidly expanding to include family entertainment and lifestyle shows, extravagant music videos, and autotuned recitations of popular poetry. With this range of products, the group targets specific audiences throughout Yemen and the region, as well as their foreign and domestic foes.

How the Houthis Changed Yemen’s Media

A crucial step in the 2014-15 Houthi takeover of Sana’a was the seizure of state-run media outlets and the silencing of political opponents and critics. The brutal suppression of independent journalism that emerged under the Houthis in 2015 continues today. Numerous reports reveal that the Houthis arrest, imprison, and torture journalists. On April 11 th, 2020,, four Yemeni journalists were convicted of espionage and sentenced to death in a Houthi court.

Many of the newspapers, TV channels, and radio stations that continue to operate under Houthi leadership are largely neglected by the group. Resources and creative energy instead are diverted to the Houthis’ flagship media network, Al-Masirah. Established in south Beirut in 2012, the network shares a close relationship with Hezbollah’s Al-Manar, and the two outlets are similar in terms of production quality and design.

The Houthis are fully aware of the crucial role that journalism plays in Yemen’s war. This is clear not only from their media output, but also from their own analysis of the topic. An op-ed published late last year by pro-Houthi journalist Zaid al-Ba’auh explains the importance of the media in times of conflict. He asserts that “one of the most important means of psychological warfare is media—whether audio, visual, or textual—because it invades people directly, especially those who have no awareness or discernment to protect themselves.”

The group regularly asserts that this form of psychological warfare is used against them by their regional and international rivals, and the Houthis are committed to instrumentalizing media as a counterweight to what they see as Saudi, American, and Israeli propaganda.

Houthi Military Propaganda and Poetry

The Houthis and their supporters have developed their own signature messaging campaigns designed to mobilize and attract followers. Popular themes include a condemnation of coalition airstrikes and praise for Houthi military successes. Footage and images that support these themes are widely shared and repurposed for a range of propaganda pieces, including Houthi-produced documentaries and fundraising campaigns.

Images of Houthi weaponry and Abdulmalek al-Houthi’s speeches are combined into a punchy propaganda piece replete with common Houthi themes, including missile strikes and Houthi soldiers performing a Nazi salute. In this example, produced by Ansar Allah Media Center and published on May 3, 2020, supporters are urged to donate to Houthi air defense systems.

Other Houthi productions are more creative and appeal to a broader audience. Possibly the most versatile and beloved form of Houthi propaganda is their poetry. Their zawamil and anasheed(singulars zamil and nasheed) are commonly described as war poems or anthems, but their subject matter ranges from international politics and religious tradition to social issues and praise of leaders. Houthi zawamil frequently include threats to Saudi Arabia, the United Arab Emirates, Israel, and the United States, and are intended to inspire followers and intimidate rivals.

Producing poetry to promote one’s cause is not unique to the Houthis. Yemen has a rich poetic tradition that is deeply embedded in the country’s political processes and conflict resolution. As Steve Caton explains in Peaks of Yemen I Summon, “To compose a poem is to construct oneself as a peacemaker, as a warrior, as a Muslim.” He adds that “the practice of composing a zamil produces a certain ideology meant to be persuasive in the arena of political conflict.” For many Yemeni factions, these persuasive ideologies can now be recited, recorded, edited, and shared faster than ever before and at an astounding volume of output thanks to mobile phones and the internet.

Zawamil and their accompanying videos are provided on Telegram channels in low, medium, and high-quality resolutions for download by a broad audience regardless of local internet quality. Zawamil are also posted on YouTube, Facebook, and SoundCloud. This zamil video was produced in late 2019 and uploaded to the Young Sa’ada Revolutionary YouTube channel.

Houthis Use of Media to Govern

Zawamil and other forms of poetry are widely circulated in Yemen and beyond. The catchy rhythms and repetitive verses are effective for getting a message to stick in the listener’s mind. Recently, poems explaining the rules for social distancing protocols to reduce the spread of COVID-19 were published and shared on pro-Houthi websites and social media. These zawamil promote sound medical advice while reminding the audience that foreign adversaries, and not Houthi officials, are to blame for the pandemic.

This zamil was released in May 2020. The first case of COVID-19 was recorded in Yemen in April and, at the time of writing, dozens of cases have been reported in governorates controlled by Yemen’s internationally recognized government. Houthi-held territories have only reported a handful of cases, though many observers claim the infection rate is much higher.

Although Houthi media encompasses a range of topics, their messaging frequently targets the United States and promotes anti-Semitic tropes. These themes are sometimes most visible when Houthi-affiliated presenters are not discussing Yemen’s conflict, but when they are commenting on social issues. An example of this can be seen on the Al-Masirah program The Mask (on air from 2012 to 2019), which analyzed popular film and television. The show’s critiques of Hollywood demonstrate a sincere appreciation for American cinema and knowledge of American history and culture. Nonetheless, the host and her guests condemn the United States on issues such as racism, while simultaneously trotting out their own anti-Semitic conspiracy theories.

A discussion of the history behind Black Panther and Marvel comics on an episode of The Mask on the Houthi-run station Al-Masirah, 2019.

Clips like these are more effective than military propaganda at highlighting Houthi messaging strategies and their broader worldview. The mere existence of a show like The Mask—one of the first programs aired on Al-Masirah—demonstrates the Houthis’ early appreciation for the utility of the entertainment industry as an instrument of soft power. The program also raises a question about the Houthis’ intended audience: Are Al-Masirah’s Lebanese host and Lebanese guests speaking to Yemenis at all?

While programs like The Mask seem far removed from the day-to-day experiences of Yemenis living through conflict, other Houthi-controlled media is tied to the needs of average citizens. In Al-Masirah’s The Field, the program’s host travels to a different Yemeni agricultural site for each episode to speak with farmers about the challenges they face due to war, climate change, and a lack of support from the Ministry of Agriculture. The Field is one example of Houthi media striving to portray the group as more than a militia, but as a social movement invested in the wellbeing of Yemenis throughout the country.

This clip is from an episode of Al-Masirah’s The Field that was filmed in the Haban district of Sa’ada governorate and aired in April of this year.

Houthi Media at the Forefront of a Movement

Among the commonly held views about the Houthis, perhaps none has served the group more effectively than the notion that their expertise is limited to the battlefield, or that they are shortsighted and lack political acumen. On the contrary, the Houthis have nearly two decades of experience in creating targeted messaging campaigns and they understand the importance of propaganda during wartime. Nonetheless, the group’s experiments in soft power are often overlooked by observers who prefer to focus solely on their military capabilities.

The Houthis’ increasingly influential media apparatus presents challenges to independent journalists in Yemen, but it also gives us important insight into the group’s evolving identities and ideologies. We can expand our understanding of the group, and the conflict in Yemen more broadly, if we familiarize ourselves with all aspects of the movement and make a real effort to hear what the Houthis have to say.

Hannah Porter is a Yemen analyst at the international development firm DT Global.

The views and opinions expressed in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of Gulf International Forum.